The Mzab

The cities of the Mzab valley (five walled ones) are exquisite apparitions in what one would think is an ungrateful, barren desert area. It is an amazing story of religious belief leading to the survival of a community and to a style of architecture marked by pastel rose, blue, and yellow quadrangular houses in concentric circles on hills, capped by an unadorned minaret sloping gradually inward toward the sky, rising from the uneven curves and arches of a simply styled mosque. The mosque is always at the center, on the highest place of a city–with an adjoining storehouse, armory, and fortress. The building materials are ochreous stones and lime (chaux), mixed with water to make a smooth finish. The old parts of these cities have a mysterious, otherworldly, calm, and orderly ambiance, held together by the pleasing sensation of the architecture, against which the people–women in their white shrouds (called haïks, only the left eye open to the outside if married), men in their pleated, baggy pantalons or long robes with hats or turbans–contribute to a pleasing artistic whole.

Ghardaia

Ghardaia is the principal settlement of the wilaya (province) of the name nowadays, where people have created cities and gardens in the midst of a labyrinth of stones and hills with minimal vegetation, through the astute management of water resources. The history of the region is linked to Kharijism, particularly the Ibadite sect. Emigrants to the Mzab following the collapse of the Rustamid state of Tahert, these puritans of the desert constitute today an important religious confederation. The Ibadites founded the city of Ghardaia after that of El Ateuf and Melika in the 11th century (1053). Located in the Mzab valley, the majority of the terrain is arid, traversed by ravines, and rocky. The climate is dry, with extremes of temperature between day and night, and between winter and summer.

The heat of the summer is immense, making it one of the hottest areas of the world. Due to persecution in past centuries, the Mozabites retreated to this difficult, uncultivated and inhospitable area of the Sahara desert, where they developed a number of oasis towns (the five ksur [walled villages]), which became collectively known as the Mzab region. The economy is dependent on agriculture and the raising of livestock, although Ghardaia is also a center of commerce and Saharan industry, such as those related to oil, water, and construction. Independent and resistant to outside interference in their affairs, the Mozabites have come to be skillful, enterprising, well-organized businessmen. As refugees finding shelter in undesirable places, the Mozabite community seems to have the ingenuity and ability to prosper wherever it goes. Networks of Mozabites in other Algerian cities as well as those around the globe provide support to fellow travelers.

Berbers of the Beni Mzab (who speak Tumzabt, a branch of the Zenati group of Berber languages), agriculturalists and herders, arrived in the region at the beginning of the 11th century. As Ibadites, they were fleeing religious persecution and sought refuge in the hostile environment of what is presently known as the Mzab. The Ibadites are the disciples of Imam Djabir ibn Zaid, who fled the region of present-day Iraq after the murder of Ali in 661 AD and settled in Tunisia. In 777 AD, Ibn Rustam founded the Rustamid state at Tahert (also known as Tiaret). At the beginning of the 900s, threatened, they found refuge in the south and founded Sedrata, the new capital of Ouargla. In 1072 AD, Sedrata was completely razed by the forces of El Mansour, a Hammadite of Bejaia; and the survivors chose to settle in the Mzab, a defensible location and an undesirable area to their persecuters.

The Mozabites built walls and ramparts around three prominent hills, crowned the mounts with a mosque, and finally constructed houses, creating the cities of El Ateuf (1012 AD), Bou Noura (1046 AD) and Ghardaia (1048 AD). Two cities were founded later: Beni Isguen (1347 AD) and Melika (1350 AD). Each city is built on a hill, high enough to escape the infrequent but violent inundations of rainwater. Six centuries later, the Mozabites established Guerrara (1631 AD) and then Berriane (1690 AD). The mixture of the functionalist purity and simplicity of the Ibadi faith with the oasian way of life led to a strict organization of land and space. Each stronghold has a fortress-like mosque, whose minaret serves as watchtower, although at least one city has a separate watchtower. Houses of uniform size and type were constructed in concentric circles around the mosque. The architecture of the Mzab settlements was designed for egalitarian communal living, with respect for family privacy. Each house has a cellar and two stories, with a center opening, exposed or covered with a window to the sky. In the summer Mozabites migrate to summer homes centered around palm grove oases, watered by specially devised irrigation, or water-sharing, systems. One of the major oasis groups of the Sahara desert, the Mzab valley is surrounded by arid country known as chebka, crossed by dry river beds.

The Ibadites have a strict code of ethics, preserved for centuries, which they seek to live by. The women wear a long white cloak, which covers most of their body, with the right eye also being covered by the cloak. A married woman who goes out in the street must be totally hidden, with only her left eye peeping through a small hole. Girls adopt the haïk at the age of 13, but can show their face until married. The men also have a distinctive traditional dress, baggy, multiple-pleated beige or navy trousers, worn with a long shirt sometimes. They will often wear a red or white cap, or sometimes a turban.

The insular nature of the Ibadites has preserved the integrity and identity of the community. They are tolerant but closed to people of other cultures, while very dependent on their own culture. One of the strongest ties that unites the group is language. Children learn the Mozabite dialect at home, study Arabic at school, and may learn some French for business reasons. Strong social control is valued; and family units (qabail) safeguard their separate identities. The qabail are strong tribal-like groups. Each one elects a magistrate or kebir and one or two sheriffs (muqaddemin). These family groupings live together in designated areas. There are strict regulations concerning the interaction of family members. A man is not permitted to see the face of his sister-in-law. Women are kept inside the houses; and a woman might not even be allowed to show her face to anyone but her husband. The women socialize on rooftops and relate only to close family members. Some women do go out to take their children to school, make small purchases, or take public transport to visit family members in another area. Women hardly ever leave the community. When men have to be away, there are women guardians who watch over the house concerned, usually the mother-in-law. There are also women clergy. Women have been taught not to raise their voices in laughter, conversation, or calling some one. They are forbidden to speak rooftop to rooftop. In shops, they do not show the palms of their hands. Men in conversation on the streets are usually in conversation with one or more men from their people group. Mozabites socialize together, but will not as a rule open their home to non-Mzab people, not even fellow Algerians.

The Ibadi Azzaba (Council of Religious Affairs) continues to dominate the social life of each city of the area. Alcohol is forbidden. The head of the Azzaba has the power to excommunicate those who infringe the moral and religious laws in the community. The Ghasilaat is the women’s form of Azzaba; this body supervises the women and settles private disputes in the community. A federal council, Majlis Ammi Said, unites representatives of the seven cities as well as Ouargla, an ancient town 120 miles southeast of the Mzab valley. This council forms a federative body for religious and social matters and represents an Islamic government unique today. All older sections of these cities require a guide for visitation; and pictures can be taken of buildings but not of people. This council rules numerous details of Ibadite social life, such as the weight of gold given as a dowry to a woman and the length and type of wedding celebrations (3-days, communal). This Islamic government rules all the details of the Ibadites’ daily life. Infringement of the rules is punished under the tabriya, which ranges from a kind of quarantine to exile. With economic, social, and political integration to Algeria, sanctions are less effective than previously and tend to have more impact on women. Ibadites no longer live in virtual isolation. Dramatic change has occurred since oil was discovered in Hassi Messaoud in 1958 and gas in Hassi R’mel in 1980. A Chinese engineer currently staying at the Djonoub Hotel (Hotel of the South) is exploring for additional oil resources. So far none have been found. With the discovery of oil and gas came outsiders with new values. The small cities of the Mzab are now commercial centers at the crossroads of southern Algeria. Thousands of Bedouin and Algerians from the north have settled outside the ramparts and between Beni Isguen, Ghardaia, and Melika. Many young men from Kabylia, for example, have come south to work in the hotel and restaurant business. As cement and iron are taking the place of the traditional building materials of Mzabite architecture, so the moral values of the Ibadites, especially the emphasis on social equality, are being eroded by the conviction that everything, which represents progress, power, art, and culture, can come only from the West. Ibadites are thus exposed to many new temptations to break the old rules. Moreover, they can today find refuge in the “foreign” community, which today makes up almost half the population of the Mzab.

Beni Izguen

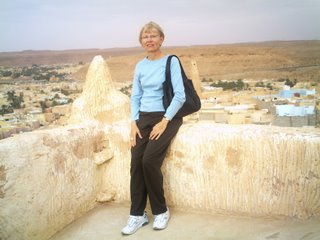

Situated on the right bank of the Mzab valley, Beni Izguen is called the religious and the secret, surrounded by ramparts with only two doors for entry. Certain of its quarters are forbidden to foreigners or outsiders. Its streets are narrow, ascending up to the quarter of Toblas, where inhabitants learn the religious laws and politics of the city. The market place of traditional crafts is picturesque, closed during Ramadan, and the watch tour offers a superb view of the other Mozabite cities. This city is supposed to be the least touched by the forces of assimilation with wider Algerian society. The city’s council of religious affairs (halka assaba) includes 12 key men of the community, the same number who sought refuge in the wadi almost 1,000 years ago. These men are the imam, the muezzin, the fuqqara (who teach in the madrassa and in the mahat [lycée]), the five men who wash the dead, and two treasurers. The council of social affairs (halka doman) includes a representative of each clan (ashira) and deals with the mundane affairs of a community, which attaches great significance to the knowledge of family trees. In Beni Isguen, the oldest clan, settled at the highest point in the city, near the watchtower, comes from a Berber family from Tafilet. Other clams claim they descend from Persian families. In Ibadite society, women are completely separated from men, spending most of their lives in their houses, while men virtually live in their shops. The main markets are the domain of men; and not many Mozabite women are seen in these areas. The women have their own council, which includes the timsiridines, the women who wash the dead.

Melika

Given the name of queen due to the purity of its architectural lines and its uniformly pink color. The Ksar, the mosque, and the cemetery of Sheikh Sidi Aissa and his family, the Palmerie with its streamlets and refreshing gardens are the attractions of the city. Most families traditionally had a house in the old city and one in the Palmerie, where they spent the hot summer months.

El Ateuf

The first city founded in the Mzab valley, it has inspired numerous architects, such as Corbusier. Its history is obvious in the carefully maintained oases and plantings of palm trees. It’s a thousand year old city, composed of rings of pastel rose, blue, and yellow quadrangular houses inclining toward the hilltop, with mosques of striking simplicity, whose unadorned but captivating minarets reach toward the sky lending to the dignity of the city. The mosque of Sidi Brahim consists of an ensemble of uneven arcades, open to the outside. It is over 7 centuries old.

Authoritarianism is the oldest and simplest form of government. Totalitarianism, as demonstrated by Ibadi rule in the Mzab, may also help a community survive. The question is whether survival is the highest of society’s goals? Community and conformity are valued over individualism and self-expression. Absolute truth is valued over diversity of opinion, essential according to J.S. Mill, since no one individual can know the entire truth about any one thing.

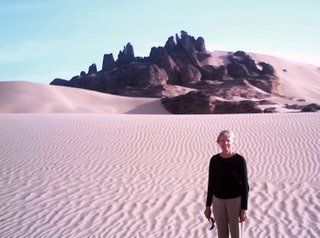

Ahmed, my tour manager, kept asking me why I had come during Ramadan. I tried to tell him I was bored, since everyone was observing Ramadan and not much was going on. However, the explanation didn’t seem to soak in. Work slows down and some services are not available that might be otherwise during la karême (the holy month). However, on the tour in Tamanrasset, this was no problem. The four-days in the desert took place as if Ramadan did not exist–for us. Mustafa, my Mzabi driver, however, made a statement that some people live only for Ramadan. All I could think of is that both he and Ahmed were from Beni Isguen (a small city, maybe 10,000 today), the least changed city of the Mzab region; and religion was indeed permeating all of their lives. Beni Isguen is a theocracy; and the requirements and duties of the faith and community come foremost and nothing else. Or it’s such a distraction that it’s hard to focus on two things at once, fasting (not to mention the revelry that follows) and work. Ahmed runs a tourism agency. Nonetheless, making money and providing services, were not at the top of the list– although I was treated in a most friendly way. For Muslims and Mzabis, fasting is required. Five prayers a day are also necessary plus the additional prayers and Qur’anic reading following the f’tour, breaking of the fast. Then the evening comes to life as shops open between 9:30 and 10:00 PM and may stay open to midnight or later. In the city squares, young boys are playing soccer and other games. Young and older men are socializing over tea or soft drinks in the plein-air cafés. People are out shopping and visiting family perhaps until 2-3:00 in the morning. In the Ghardaia area, everyone knows everyone else. Now, is the time to enjoy oneself before another round of fasting sets in. But people are feeling its effects. The guards at the hotel lobby entrance are dozing off. The taxi driver returned me to my hotel, driving and staring straight ahead into the night through the windshield, focused solely on the line in the road or traffic ahead in a sort of trance. My big piece of luggage was too heavy for him to hoist alone; yet the bellhops were off tending to post-f’tour and prayer events. The only ones who seem to be thriving on Ramadan are the young for whom it is going all too fast.

I’m a bit bewildered by it all. Religious duties may be important; but from a modern perspective, Ramadan causes a lot of economic and academic disruption as people move into slow gear during the daylight hours. But that doesn’t seem to enter into anyone’s consciousness here. Islam is part of the country’s heritage. It’s obligations are sacred. The pull of the collective is what calls and no more strongly than in the Mzab. During Ramadan, Muslims get up later, walk and move more slowly, perform their duties less energetically, for less time, or not at all. A whole society locks into gear around a religious belief and generally believes that the majority should rule and others should follow suit. Foreigners can get meals in hotels or try to live their lives in what they consider an interesting way. Yet, except for a few other outsiders, not yet too common in Algeria, or a few more liberal Algerians, or a few tour guides who perform beyond the call of duty, you are largely left on your own. Surprisingly, OPEC decided to curb supplies of oil before the end of Ramadan.

The last two pictures of the mosque are where the women sit. The one prior to that shows part of the men's area.

Oil

Oil