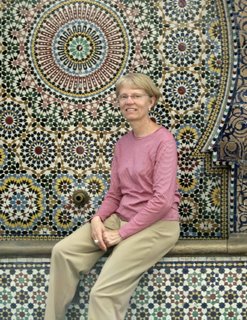

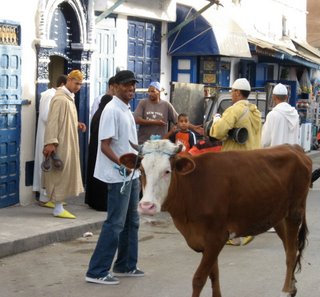

It has been described as an historical and archeological treasure, designated part of the world's cultural heritage by UNESCO, and referred to as the soul of Algiers. Yet, the Casbah has suffered from neglect and the ravages of time. People live in it, selling wares in the Lower Casbah, and buying essentials and gathering water from public fountains in the Upper Casbah. Individual homes have filled in their wells; so women and children can be seen at the tile-decorated common water spouts, filling plastic jugs for household water. Connected and leaky hoses run down the littered alleys and stairways, speeding up the transfer of this potable and valuable resource. Constructed on a hillside, the Casbah is connected by a series of walkways and flights of steps. Workers load plastic sacks full of debris onto the backs of donkeys and carry them away. Cars can't drive into the area's inner sanctums. Hints of its former glory can be seen in portions of homes, which retain the white stucco façades and balconies, held up by dark-brown hardened, slanting poles. A few three to four story homes have collapsed. From a rooftop terrace, I could look out over the dilapidated rooftops toward the bay. It took some imagination to bring the Casbah to life through its historical characters. It was originally a Berber town, founded by Bologhine Ibn Ziri, a Zirid prince, in the 10th century. A statue of him stands in one the nearby "rond points." From there, conquerors came and went: Maghribi contenders for power, the Spanish, the Turks, and then the French. Kheireddine Babarossa stands out as one of the greats, as founder of the Regency of Algiers and a Grand Admiral of the Ottoman fleet. Part of an old wall, mosques, and the palaces of deys, in assorted states of reconstruction and repair, bear witness to the past. Perhaps, the terrorism of the 1990s left little time for attention to history and culture. I'm one of the first Fulbright scholars to come here after these years. My guides, necessary due to the crime in the Casbah, spoke little French. They said that they liked their country, Algeria, but that the Algerian people were: ?. With this, they couldn't find the right expression; they waved their hands and implied there was a problem. The director of

Iqraa (Read, the first word of the Qur'an), a program to combat illiteracy had made the same comment. The Upper Casbah is interesting wth its several-storied homes wth terraces,its mosques, its

zaouias (tombs of holy men), and narrow streets interconnected with staircases. Children play in the lanes or can be heard shouting behind its wooden doorways. The crescent, symbol of Islam, is popular as a carved decoration. Veiled women stand out; but women in Algeria wear a wide range of clothing. Upon entering the small

zaouia of Sidi AbdeRahman (after leaving one's shoes at the door or taking a blue plastic bag from an attendant, putting them in, and keeping them with you), I noticed the number of people sitting along its walls, reflecting or making supplication to the saint. A green satin cloth covered the saint's white marble bier. Men sat on one side of the tomb on the carpeted floor nearest the entry, women sat on the other. The men's circle had a large stack of books in its midst. Women arrived accompanied and occasionally with children in tow. The atmosphere was reverential with a stand for incense and locked boxes for donations. A person in a shiny pink satin

jellabah,with hood drawn up over the head, faced the

mihrab in devotion, remaining there the entire time I was in the shrine. My guides pointed out that unmarried women, especially, came to the shrine to ask for a good man to marry. Actually, it's Sidi Flih, whose tomb, along with those of others, is adjacent, who is known for this. The guides also said that they believed that God answered a person's requests and needs, not a saint. In conversation with a man in the street, they learned that post of the visitors to the shrine come from outside Algiers. The visit to the

zaouia was the most interesting part of my visit to the Casbah. It was living history-Algerians visiting a holy place to meet their spiritual needs. Leaving the Casbah, I came out on Martyrs' Square, adjacent to the New Mosque and the Grand Mosque, constructed in the 11th century. There was so much more I wanted to know; but it was going to take more than one quick visit to the Casbah with guides who had more expertise in security than history. However, it was a beginning; and my fascination with Algeria and its people continues.

It has been described as an historical and archeological treasure, designated part of the world's cultural heritage by UNESCO, and referred to as the soul of Algiers. Yet, the Casbah has suffered from neglect and the ravages of time. People live in it, selling wares in the Lower Casbah, and buying essentials and gathering water from public fountains in the Upper Casbah. Individual homes have filled in their wells; so women and children can be seen at the tile-decorated common water spouts, filling plastic jugs for household water. Connected and leaky hoses run down the littered alleys and stairways, speeding up the transfer of this potable and valuable resource. Constructed on a hillside, the Casbah is connected by a series of walkways and flights of steps. Workers load plastic sacks full of debris onto the backs of donkeys and carry them away. Cars can't drive into the area's inner sanctums. Hints of its former glory can be seen in portions of homes, which retain the white stucco façades and balconies, held up by dark-brown hardened, slanting poles. A few three to four story homes have collapsed. From a rooftop terrace, I could look out over the dilapidated rooftops toward the bay. It took some imagination to bring the Casbah to life through its historical characters. It was originally a Berber town, founded by Bologhine Ibn Ziri, a Zirid prince, in the 10th century. A statue of him stands in one the nearby "rond points." From there, conquerors came and went: Maghribi contenders for power, the Spanish, the Turks, and then the French. Kheireddine Babarossa stands out as one of the greats, as founder of the Regency of Algiers and a Grand Admiral of the Ottoman fleet. Part of an old wall, mosques, and the palaces of deys, in assorted states of reconstruction and repair, bear witness to the past. Perhaps, the terrorism of the 1990s left little time for attention to history and culture. I'm one of the first Fulbright scholars to come here after these years. My guides, necessary due to the crime in the Casbah, spoke little French. They said that they liked their country, Algeria, but that the Algerian people were: ?. With this, they couldn't find the right expression; they waved their hands and implied there was a problem. The director of Iqraa (Read, the first word of the Qur'an), a program to combat illiteracy had made the same comment. The Upper Casbah is interesting wth its several-storied homes wth terraces,its mosques, its zaouias (tombs of holy men), and narrow streets interconnected with staircases. Children play in the lanes or can be heard shouting behind its wooden doorways. The crescent, symbol of Islam, is popular as a carved decoration. Veiled women stand out; but women in Algeria wear a wide range of clothing. Upon entering the small zaouia of Sidi AbdeRahman (after leaving one's shoes at the door or taking a blue plastic bag from an attendant, putting them in, and keeping them with you), I noticed the number of people sitting along its walls, reflecting or making supplication to the saint. A green satin cloth covered the saint's white marble bier. Men sat on one side of the tomb on the carpeted floor nearest the entry, women sat on the other. The men's circle had a large stack of books in its midst. Women arrived accompanied and occasionally with children in tow. The atmosphere was reverential with a stand for incense and locked boxes for donations. A person in a shiny pink satin jellabah,with hood drawn up over the head, faced the mihrab in devotion, remaining there the entire time I was in the shrine. My guides pointed out that unmarried women, especially, came to the shrine to ask for a good man to marry. Actually, it's Sidi Flih, whose tomb, along with those of others, is adjacent, who is known for this. The guides also said that they believed that God answered a person's requests and needs, not a saint. In conversation with a man in the street, they learned that post of the visitors to the shrine come from outside Algiers. The visit to the zaouia was the most interesting part of my visit to the Casbah. It was living history-Algerians visiting a holy place to meet their spiritual needs. Leaving the Casbah, I came out on Martyrs' Square, adjacent to the New Mosque and the Grand Mosque, constructed in the 11th century. There was so much more I wanted to know; but it was going to take more than one quick visit to the Casbah with guides who had more expertise in security than history. However, it was a beginning; and my fascination with Algeria and its people continues.

It has been described as an historical and archeological treasure, designated part of the world's cultural heritage by UNESCO, and referred to as the soul of Algiers. Yet, the Casbah has suffered from neglect and the ravages of time. People live in it, selling wares in the Lower Casbah, and buying essentials and gathering water from public fountains in the Upper Casbah. Individual homes have filled in their wells; so women and children can be seen at the tile-decorated common water spouts, filling plastic jugs for household water. Connected and leaky hoses run down the littered alleys and stairways, speeding up the transfer of this potable and valuable resource. Constructed on a hillside, the Casbah is connected by a series of walkways and flights of steps. Workers load plastic sacks full of debris onto the backs of donkeys and carry them away. Cars can't drive into the area's inner sanctums. Hints of its former glory can be seen in portions of homes, which retain the white stucco façades and balconies, held up by dark-brown hardened, slanting poles. A few three to four story homes have collapsed. From a rooftop terrace, I could look out over the dilapidated rooftops toward the bay. It took some imagination to bring the Casbah to life through its historical characters. It was originally a Berber town, founded by Bologhine Ibn Ziri, a Zirid prince, in the 10th century. A statue of him stands in one the nearby "rond points." From there, conquerors came and went: Maghribi contenders for power, the Spanish, the Turks, and then the French. Kheireddine Babarossa stands out as one of the greats, as founder of the Regency of Algiers and a Grand Admiral of the Ottoman fleet. Part of an old wall, mosques, and the palaces of deys, in assorted states of reconstruction and repair, bear witness to the past. Perhaps, the terrorism of the 1990s left little time for attention to history and culture. I'm one of the first Fulbright scholars to come here after these years. My guides, necessary due to the crime in the Casbah, spoke little French. They said that they liked their country, Algeria, but that the Algerian people were: ?. With this, they couldn't find the right expression; they waved their hands and implied there was a problem. The director of Iqraa (Read, the first word of the Qur'an), a program to combat illiteracy had made the same comment. The Upper Casbah is interesting wth its several-storied homes wth terraces,its mosques, its zaouias (tombs of holy men), and narrow streets interconnected with staircases. Children play in the lanes or can be heard shouting behind its wooden doorways. The crescent, symbol of Islam, is popular as a carved decoration. Veiled women stand out; but women in Algeria wear a wide range of clothing. Upon entering the small zaouia of Sidi AbdeRahman (after leaving one's shoes at the door or taking a blue plastic bag from an attendant, putting them in, and keeping them with you), I noticed the number of people sitting along its walls, reflecting or making supplication to the saint. A green satin cloth covered the saint's white marble bier. Men sat on one side of the tomb on the carpeted floor nearest the entry, women sat on the other. The men's circle had a large stack of books in its midst. Women arrived accompanied and occasionally with children in tow. The atmosphere was reverential with a stand for incense and locked boxes for donations. A person in a shiny pink satin jellabah,with hood drawn up over the head, faced the mihrab in devotion, remaining there the entire time I was in the shrine. My guides pointed out that unmarried women, especially, came to the shrine to ask for a good man to marry. Actually, it's Sidi Flih, whose tomb, along with those of others, is adjacent, who is known for this. The guides also said that they believed that God answered a person's requests and needs, not a saint. In conversation with a man in the street, they learned that post of the visitors to the shrine come from outside Algiers. The visit to the zaouia was the most interesting part of my visit to the Casbah. It was living history-Algerians visiting a holy place to meet their spiritual needs. Leaving the Casbah, I came out on Martyrs' Square, adjacent to the New Mosque and the Grand Mosque, constructed in the 11th century. There was so much more I wanted to know; but it was going to take more than one quick visit to the Casbah with guides who had more expertise in security than history. However, it was a beginning; and my fascination with Algeria and its people continues.