Land of the Lotus Eaters

Djerba

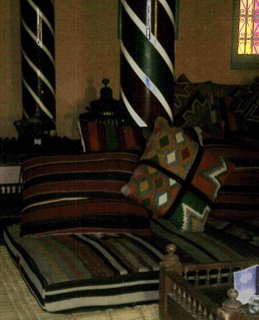

DjerbaAn island of villages, outside of the principal administrative town, Houmt Souk (Berber for market village), many visitors are swept away by the isle’s charms, much as those seduced by the Lotus-eaters in Homer’s Odyssey. On a stopover on the island, Ulysses’ fellow travelers ate of the honey-flavored blossoms, forgot all about their own country, and thought of nothing but remaining on the island and enjoying their state of bliss. While no lotus flowers are found in the area; the seductive power of the environment remains. Palm and olive trees, white mosques and koubas, Djerbian menzels (traditional homes), clean water, and powdery golden sand beaches continue to cast their spell in the present. The country is like a big oasis.

It’s raining today. Many of the buildings, even the tourist hotels, leak, built as they are for a mostly dry and warm climate. The winds and waves are fiercer but alluring in their unpredictability. The sea here in the lower part of the Gulf of Gabès is clear and can take on an aloe vera or olive green or be an overall bluish gray. The sun, the rain, and the clouds interrelate in bewitching behaviors.

La Ghriba

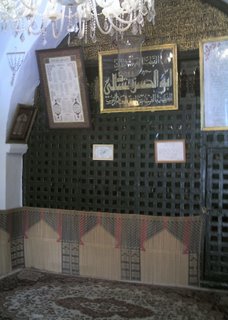

La GhribaLa Ghriba is one of the oldest and most famous synagogues of the Maghrib. A portion of the Jewish community has existed on Djerba since the first century, after Titus destroyed Jerusalem. Welcomed by the island’s Berbers, Jews adopted some of their customs, even several bordering on the superstitious. It is now greatly reduced, since the creation of the state of Israel. Today, the Djerbian Jewish community has about 650 members, almost all of them living in Er Rhiad. Security is extremely tight around the synagogue, as one might expect after the bombing several years ago. The exterior is simple, a rectangular building with blue trim in the Tunisian style. Visitors have to cover their heads and remove their shoes to enter. Rabbis are present in a corner, spending the day chanting and reciting the psalmody. In a profound spiritual ambiance, I treasured the decorative tiles and light filtering through colored windows. The synagogue houses one of the oldest Torahs in the world. The original Jewish community of Djerba brought it, when they came in 586 BC, after Nebuchadnezzar destroyed Jerusalem and deported the population. Some returned when Cyrus, king of the Persians, allowed Jews to go back to the holy city in 539. Many remained; while retaining their religion and their tribes, they became Arab in the sense of adopting Arab names as well as the language. They never, however, converted to Islam. The two communities have an understanding. They go to the same schools, may work together; but they never intermarry and children attend their respective community’s religious schools in the evening. For Jews and Muslims alike, it is important to read their sacred literature.

Guellala

GuellalaGuellala, located on the southern coast of the islet on the Gulf of Bou Grara, is known for pottery production, the beneficiary of the clay in its soil. As many traditional crafts, pottery making has suffered in quality due to its orientation toward the tourist trade. The flamingos and herons visible along the shoreline are a highlight of the trip. Next, the simple white mosque, constructed of earth, lime, and stone joins others as a symbol of Djerbian style and serenity. The Museum of Djerbian Heritage is one of the best I have seen. All white with beautiful gardens, displays trace scenes from daily life on Djerba. All the stages of marriage are presented, from the preparation of the bride to the following ceremonies. I also saw a camel drawing an olive oil press, a Sufi ceremony, circumcision rites, and a small marabout shrine. Music accompanies the visit.

Mahboubine

MahboubineSupposedly the Fadhloum Mosque is the oldest on Djerba. Originally Ibadite, it was taken over by Malekites. It is difficult to know how many Ibadis there presently are. They have become secretive due to past persecutions; and outwardly blend in with the Maleki Sunni community. Some evidence suggests that it dates from the 14th century. It housed a Qur’anic school, complete with bakery and mill. This structure has small domes in the manner of Djerbian menzels. I returned to the hotel through the countryside, driving in the midst of orchards and olive trees, one of which is supposed to be 800 years old.

I learned that women working in the hotel business here are from the mainland, not from Djerba.